- map

- how you can help

- FAQ's

- contact

- copyright

-

ahnentafel and citation # display:| |

|

Previously, I believed that the parents of 1050811Joan ___ were 2101622Thomas de Dene and 2101623Martha de Shelving. However, researcher Pete Andrews called my attention to 2101622Thomas' inquisitions post mortem, which I had overlooked. 2101622Thomas' two IPM's strongly suggest that he is not 1050811Joan's father (since the IPM explicitly notes 2101622Thomas' daughter Joan as deceased in early childhood, among other incongruences). Nevertheless, because 1050811Joan certainly seems to be related to 2101622Thomas in some manner, and because my older work could prove useful for future research, I've isolated the profile pages that I'd written for 1050811Joan's formerly proposed ancestors into a separate section of my website, starting from the old version of Joan's page onward. You can see a list of those ancestors or a family tree of them. |

| Snapshot: | royal servant; conspirator in the assassination of Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury |

| Parents: | 538015388Oyn Porcell His mother's identity is unknown. |

| Born: | unknown |

| Last known record: | 1176 was pardoned for a debt at Angmering, Sussex, England |

| Buried: | supposedly at the Château de Vernay, Airvault, France, although the evidence is not at all conclusive The château's coordinates: N46.817584 E0.151654 |

A record describes ⁊ marescall suo").

| Excerpts from Barlow's Thomas Becket | ||

| Page | Excerpt | Chapter:Citation |

|---|---|---|

| 114 | [After violating the Constitutions of Clarendon and several deliberately provocative acts, Thomas Becket was called to court at Northampton Castle on 8 October 1164, but refused to accept its judgment.] While the justiciar faltered, Thomas rose, went out of the chamber and passed through the halls to shouts of 'perjuror' and 'traitor'. Among his revilers were [...] Ranulf de Broc [...]. Ranulf, hereditary doorkeeper of the king's chamber and keeper of the royal whores, was, with his clan, the Brokeis, to play an important role in the archbishop's life and death. Thomas answered their taunts with abuse: [...] a kinsman of Ranulf had been hanged for a crime. Miraculously Thomas and his clerks managed to escape from the castle through a locked gate [...] | 6:55(abbreviations) |

| 124-125 | [Thomas Becket fled to France. While he was away, King Henry II seized his property in England.] On Boxing Day Henry started to take his revenge on Thomas and his supporters, real and presumed. He ordered the confiscation of all Thomas's possessions and the forfeiture of the archbishopric. [...] The archbishopric was granted retrospectively from Michaelmas to a trusted royal servant, Ranulf de Broc, with whom Thomas bandied insults at Northampton, for an annual farm of £1,562 5s. 5½d., and he retained the custody until Michaelmas 1170. The day-to-day administration he entrusted to his clerk and kinsman, Robert de Broc, alleged to be a renegade monk, who built a house at Canterbury out of timber taken from the archbishop's woods. William of Canterbury describes him feasting there with his friends at Christmas 1170 and sharing the food with their dogs. Ranulf and Robert were efficient custodians, only £13 8s. 6d. in debt to the king at the hand-over; and this was pardoned by Henry at Michaelmasn 1172. | 7:14 |

| 126 | On Boxing Day Henry also ordered the proscription and exile of all Thomas's relations and members of his household, both clerical and lay, together with their families. In order to stifle opposition, all appeals to the papal curia were prohibited. [...] On Sunday 27 December Ranulf de Broc and other royal servants travelled to London, and, taking possession of the archiepiscopal residence at Lambeth, ordered the arrest of all Thomas's relatives, clerks and servants and all of those who had given him aid during his flight from Northampton.

[...] Ranulf de Broc compelled most of those he arrested to take an oath that they would leave the kingdom immediately and proceed directly to the archbishop at Pontigny [i.e., to Thomas Beckett]. The exiled kindred included women, children and servants, clearly whole families. |

7:17 |

| 175-176 | One vexation for Thomas was the conduct of his monks at Canterbury after the death of Prior Wilbert on 27 September 1167. They allowed Ranulf de Broc, the royal custodian of the see, to intrude even more, and 'traitors' with the convent regularly disclosed to him, and so to the king, anything said or done in Thomas's favour in the secret meetings of the chapter. John of Salisbury was given by Thomas the task of disciplining the monks, and he wrote some unusually scathing letters. | 9:16 |

| 184 | [Thomas Becket travelled] to St Bernard's foundation at Clairvaux [...] and on 13 April [...] excommunicated ten persons whose offences he considered notorious. These were [...] Ranulf de Broc and his nephew Robert [and others]. Ranulf, Thomas and Hugh had been excommunicated at Vézelay in 1166 [...] None of these ten seems to have been specially warned or cited [...] | 9:33 |

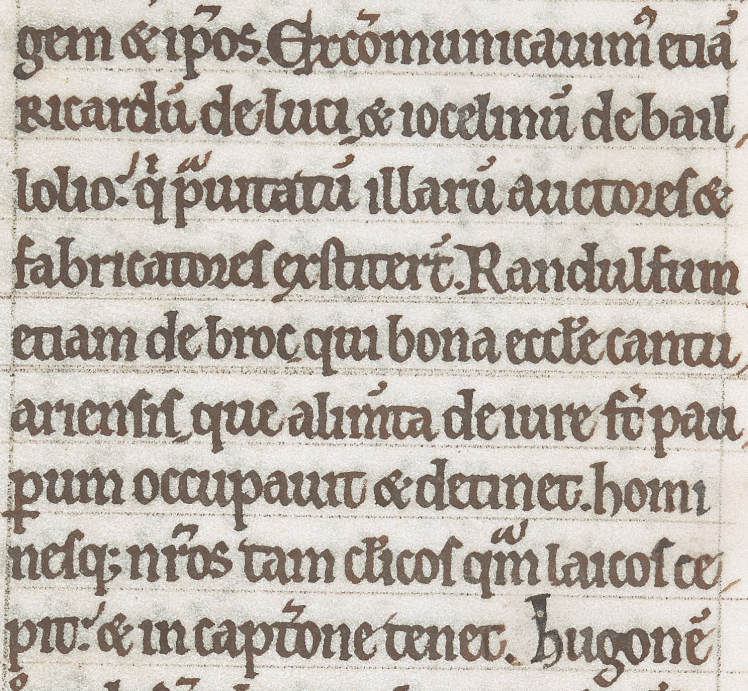

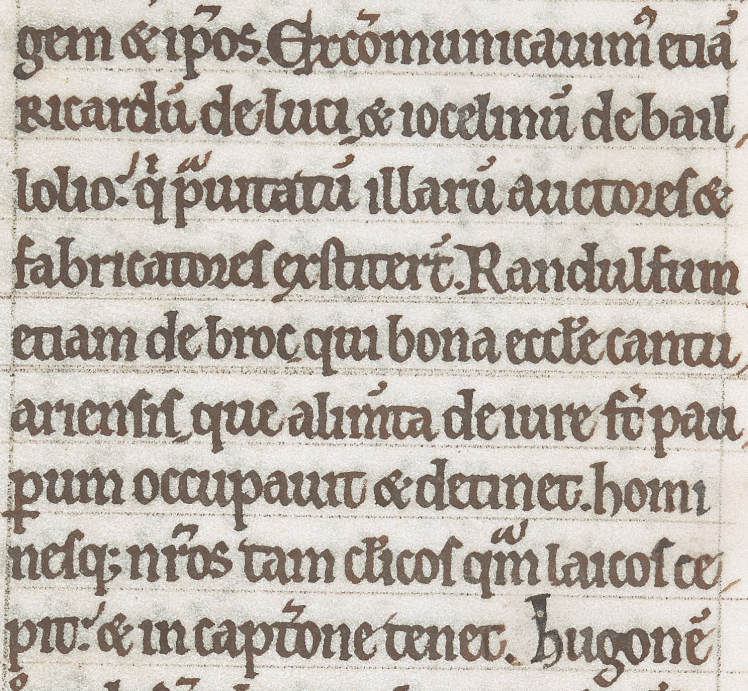

English translation: [...] We also excommunicated Richard de Luci and Jocelinus de Baillol, who were authors and fabricators of those perversions; also Randulf de Broc, who has seized and detains the goods of the church of Canterbury, which are by right the food of the poor, and our men, both clerics and laymen, he has captured, and holds in captivity [...]

| Excerpts from Barlow's Thomas Becket (continued) | ||

| Page | Excerpt | Chapter:Citation |

|---|---|---|

| 216 | [Thomas Becket sought peace with the king, and a restoration of Becket's property was pending—until it was delayed...] One of the 'abominations' was that Ranulf de Broc was using the delay to strip the archiepiscopal estates of all their stores and stockpile them in Saltwood castle. The weather remained very warm and the harvest had presumably been good. Thomas wrote to Henry to complain of the spoliation and urged him to intervene and expedite the restoration. He feared he would have nothing to live on if there was much more delay. | 10:37 |

| 220-221 | On 15 November Thomas sent John of Salisbury to England. He was to represent him at a synod [...] at which those laymen and clergy who had incurred excommunication by contagion would be absolved. [...] By thus cleansing all those who had been forced to do business with Ranulf de Broc and Geoffrey Ridel and their subordinates, Thomas's return was made socially possible. But John discovered that the lands had been stripped of their moveables and the farms of their buildings, that the churches were still occupied by intruders [...], that rents due at Christmas had been collected in advance [...]. Even worse, three days before his arrival, that is to say a day or two after Martinmas, Ranulf de Broc's men had expelled Thomas's proctors and taken the estates back into royal custody. [...] The Exchequer accounts tell a rather different story. [...] the Exchequer affected to believe that Ranulf had handed over to the archbishop's agents at Michaelman 1170 and that Thomas then enjoyed the revenues, assessed at some £400, until his death three months later, when the fief reverted to royal custory. The official figures simply ignore how difficult it had been in October to prise the estates out of Ranulf's hands. | 10:45,46 |

| 225 | Hardly had Thomas and his company disembarked at Sandwich when the three principal royal officers in Kent, alerted at dawn, rode up in command of troops who were mailed and armed under their cloaks and tunics. John of Oxford confronted them bravely (Thomas generously informed the pope of his services), and only when they disarmed would he allow Gervase of Cornhill, the sheriff, Ranulf de Broc, the custodian of the archbishopric, and Reginald of Warenne to have an interview with his charge. Thomas did not rise to greet them, an offensive but understandable gesture, and firmly resisted their demand to investigate his company. His refusal, on principle, to allow one alien in his suite, Simon archdeacon of Sens [...], to take an oath of fealty to the king, as required under the blockade regulations, provoked angry words from the officials about his conduct in general. Gervase complained that, instead of peace, he had brought fire and sword into the kingdom, that he wanted to un-crown the new king and had punished all the bishops only for doing their duty to the monarch. Unless he was more careful, something would happen that had better not. Thomas answered that he was not cancelling the illegal coronation but simply punishing the bishops for having performed it contrary to God and the dignity of Canterbury. And when he added that the senior king had authorized the punishment, they quieted down a little, although they continued to demand that he should absolve the prelates. He explained that the sentences were the pope's, not his, and that he had no authority in the case. | 11:1 |

| 229 | And, while [Becket] was still in London, he received a message from Canterbury urging him to return. One or more of his ships, laden with wine, a present from the senior king, on arriving at Pevensey in east Sussex had been destroyed by Ranulf de Broc, the sailors either killed or imprisoned in the castle and the cargo seized. | 11:7 |

| 231 | Things were going from bad to worse. [Becket's] 'roaming around the country' in defiance of the royal prohibition must further have alarmed and enraged the government. Signs of hostility were mounting. Ranulf de Broc and Gervase of Cornhill cited the senior clergy and leading citizens of London to a meeting in order to discover who had welcomed Thomas to the city. But, apparently, it came to nothing [...] | ? not stated |

| 232-233 | On Christmas Eve Thomas celebrated the night Mass and read the lesson from the first chapter of St Matthew's Gospel. On the Nativity itself he preached to the people assembled in the nave of the cathedral on the text, 'Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace to men of good will' (Luke 2: 14, Vulgate text), which was one of the Lessons for the day. Unfortunately we are not told whether he used French or English. And, to prepare for the anathemas he was to pronounce, he spoke of the archbishops who were saints, particularly of the confessors and especially of St Ælfheah, the one martyr. St Alphege's church was across the road from the palace, a constant reminder to the archbishops. 'Soon there will be another martyr,' he is believed to have said. Then, after the customary prayers for the pope and the peace and propserity of the people, he excommunicated all violators of the rights of his church and the fomentors of discord in general, and named Robert and Ranulf de Broc [and others], all previously excommunicated in April-May 1169. He also announced the sentences which had been imposed on the prelates involved in the illegal coronation. 'May they all be damned by Jesus Christ,' he intoned as he hurled the flaming candles to the floor. | 11:13 |

| 237-238 | When the four barons arrived at Saltwood castle on the evening of Monday, 28 December, they found only the castellan's wife at home, for Ranulf de Broc, warned of their crossing, had gone out to meet them and also put his forces on the alert. The five then spent the night making plans. The scheme they devised was to surround the cathedral complex in order to prevent Thomas's escape and apply pressure on him to absolve the bishops, give pledges of good behaviour and, perhaps, prepare to stand trial. At some point Ranulf called out the garrisons of Dover, Rochester ('Rophe') and Bletchingley (a Clare castle in Surrey), presumably ordering them to join him at Canterbury. One the Tuesday morning, no doubt at dawn, 8 o'clock, leaving only two boys behind at Saltwood, they set off for the city, and easy ride of some two-and-a-half hours up the old Roman road, Stone Street. They mobilized other knights en route, and, before entering the city, called in on the abbot of St Augustine's in order to take his advice. Since Clarembald was no friend of Thomas's, he may well have blessed the project, short of recourse to physical violence. Indeed, he provided a knight, Simon de Criol, to whom fitzUrse was to assign a special task. Somewhere, perhaps in the abbey, the royalists must have had a meal and a drink. All the leaders, and especially the visitors, who had been traveling almost non-stop for at least three days and nights, must have been extremely tired, so fatigued that they appeared to be drunk. And the rashness of their behaviour may be attributed in part to this. When they entered the city with their small army, they first ordered the citizens to take up arms and converge on the archiepiscopal palace. But when these showed reluctance, they were ordered to stay quiet and keep out of the way of the soldiers. It would seem that Ranulf de Broc retained overall command of the besieging force, while the four barons, led by Reginald fitzUrse, with about a dozen knights and some other helpers [...] went on to deal with the archbishop. | 11:19 |

| Excerpts from Barlow's Thomas Becket (continued) | ||

| Page | Excerpt | Chapter:Citation |

|---|---|---|

| 248 | [Four barons had just murdered Becket in the church.] The four barons left the church immediately, again shouting, as they cleared a way with the flat of their swords, 'Reaus!, royal knights, king's men, king's men!' A monk was stunned, a French servant of the archdeacon of Sens wounded. The barons rejoined Robert de Broc in the palace and completed its pillage. Their primary aim was to search for papal letters and privileges — evidence of treason — and all books and documents they found they handed over to Ranulf de Broc for transmission to the king overseas. But they also beat the servants and took everything of value, including horses, which they removed while retreating through the stables, and these spoils they divided among themselves. William fitzStephen estimated the damage at more than 2,000 marks. Eventually they retired for the night to Saltwood castle. | 11:31 |

| 259 | Some months after the murder Henry replaced the Brokeis at Canterbury by new custodians, John Mauduit and Thurstin fitzSimon; but the displaced servants were not, of course, in royal disgrace and continued to prosper elsewhere. In October 1173 Ranulf was holding Haughley castle in Suffolk (unsuccessfully) for the senior king against the rebels, and he witnessed a royal charter in 1176. He built up his estates in the Godalming-Guildford area, and these with his two serjeanties went at his death through Edeline, the eldest of his five daughters and co-heirs, to her husband, Stephen of Thornham. [...] It is not known whether the Brokeis blamed St Thomas for the shortage of sons in the family. One of the clan, probably Ranulf, founded a chapel in honour of the martyr in the castle of Vernay at Airvault in Poitou. | 11:14 |

As Barlow mentions, there was a revolt against King Henry II in 1173.

Researchers often claim that

As Barlow mentions, some of the Becket assassination conspirators allegedly founded/supported a memorial chapel dedicated to Thomas Becket in Airvault, France, although I've been unable to find much (or any) reliable, primary evidence to support this claim, nor have I found any other evidence that

Although probably not the original structure, Château de Vernay today stands at coordinates N46.817584 E0.151654, about a kilometer southwest of Airvault.

Although probably not the original structure, Château de Vernay today stands at coordinates N46.817584 E0.151654, about a kilometer southwest of Airvault.

| * | In 1156 |

1: Thomas Duffus Hardy, ed., Rotuli chartarum in Turri Londinensi asservati (1837), page 160, right column

2: H. C. Maxwell Lyte, Liber Feodorum: The Book of Fees Commonly Called Testa de Nevill [...]: Part I, A.D. 1198-1242 (London, 1920), page 67

3: Curia Regis Rolls of the Reign of Henry III (1938; Kraus reprint, 1971), page 135. This is volume 8 of the Curia Regis series, although the title page doesn't specify so. You can see a copy of select pages here or a (somewhat low-quality) machine translation to English. The most pertinent phrases are "Ranulfi del Broc patris predictarum Edeline et Sibille" and "Damete de Gorum matris ipsarum Edeline et Sibille."

4: Thomas Duffus Hardy, ed., Rotuli Litterarum Clausarum in Turri Londinensi, Volume I (1833), page 4, right column, 2

5: Frank Barlow, Thomas Becket (California, 1986), page 114

6: Matthew Chadwick, "Saltwood Castle" (online image), Geograph, <https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/5122615>, accessed 24 September 2022. Mr. Chadwick has shared this image under a Creative Commons BY-SA 2.0 license.

7: Robert Bartlett, England under the Norman and Angevin Kings, 1075-1225 (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 2000), page 257

8: David Gill, "De-silting of the Moat at Haughley Castle, Haughley, HGH 046," report # 2012/127, Suffolk County Council Archeological Service; <https://suffolkarchaeology.co.uk/reports/grey-literature/de-silting-of-the-moat-at-haughley-castle>, accessed 25 September 2022. As of November 2023, the domain is no longer online/active, but fortunately I saved a copy of the archaeologists' report before it went down.

9: The Great Roll of the Pipe for the Twenty-Second Year of the Reign of King Henry the Second, A.D. 1175-1176, page 204

10: Robert Favreau, Jean Michaud, Edmond-René Labande, "I. Poitou-Charentes. 1. Ville de Poitiers. Corpus des inscriptions de la France médiévale, 1)," CNRS Editions, 1974, pages 1-42, <https://www.persee.fr/doc/cifm_0000-0000_1974_cat_1_1>, accessed 26 September 2022. I've extracted the relevant pages.

11: Joseph Hunter, ed., The Great Rolls of the Pipe for the Second, Third, and Fourth Years of the Reign of King Henry the Second, A.D. 1155, 1156, 1157, 1158 (London, 1844), page 55

12: ibid., page 174