- map

- how you can help

- FAQ's

- contact

- copyright

-

ahnentafel and citation # display:| |

| Snapshot: | pilgrim; Magna Carta baron |

| Parents: | 67251976Geoffrey de Say 67251977Alice de Cheny |

| Born: | circa 1180 location unknown |

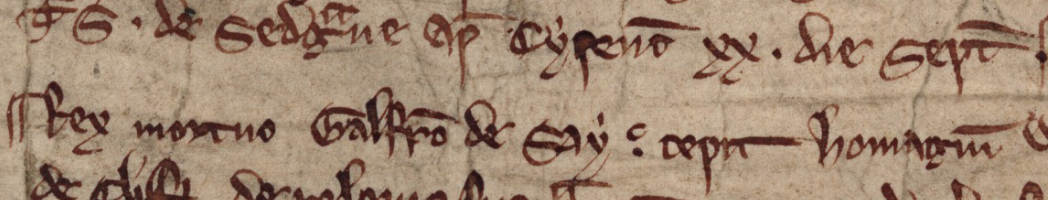

| Died: | by 20 September 1230 somewhere in (what is now) northwest France |

| Buried: | very likely in or near the Maison Dieu hospital, Dover, Kent, England Maison Dieu coordinates: N51.128 E1.3089 |

|

The following profile of |

When was In an 1180 record, In late 1775, Hugh de Periers seems to have been preparing for his impending death: In a deed, he makes preparations to give land monachis de Wenloc ("to the monks of Wenlock") pro salute animæ meæ ("for the safety of my soul"). In addition to the 1180 record mentioned above (wherein 67251976Geoffrey's wife is mentioned as uxore Hug̃ de Periers), in a different 1180 record 67251976Geoffrey mentions his wife by name: "Adelisa de Chemey." From these few records, one can conclude that 67251977Alice had been married to Hugh de Periers, who died around late 1775, and then 67251977Alice subsequently married 67251976Geoffrey by 1180. A record dated 1 January 1198 or 1199 indicates that Judging from the above evidence, it seems likely that |

Whom did The following is copied from: Douglas Richardson, Royal Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families, 2 New research indicates that Geoffrey de Say, the Magna Carta baron, actually married Hawise de Clare, daughter of Richard de Clare, Earl of Hertford. Gerald Paget notes that Geoffrey de Say had scutage of the knights fees 7 March 1215, which he held of the Earl of Clare in free-marriage (see Paget Baronage of England (1957) 485: 3-4 (sub Say), cites C. 16 John m. 7.) About 1235 Geoffrey's widow, Hawise, and their son, Willam de Say, jointly issued a charter regarding property in Edmonton, Middlesex (see O'Connor Cal. Cartularies of John Pyel & Adams Fraunceys (Camden Soc. 5 |

In June 1215

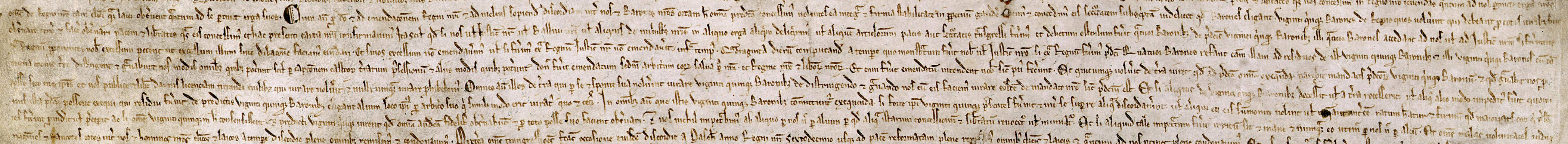

The barons' responsibilities are described in the Magna Carta's 61

The barons' names aren't specified in the Magna Carta itself, nor is there an extant primary record of such, but four early sources attest their names. One of these is copied below.

Despite having signed the Magna Carta, a bitter King John hired foreign mercenaries and launched a harsh campaign of retribution, hunting the barons (some of whom fled into exile) and burning villages all over England. On 15 October 1215 nearly all of

Perhaps worn out after years of rebellion and war, in 1219

In the late 1220's

In April 1230

His body was repatriated and buried apud Dovere (Latin for "near Dover"),

1: John Caley et al., eds., Monasticon Anglicanum: A New Edition [...], Volume VI, Part 2 (London, 1846), page 913, entry XV. The key phrases are "ego Galfridus de Say" and "pater meus Galfridus de Say, et Aliz mater mea."

2: Calendar of Documents Preserved in France, Illustrative of the History of Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 1: A.D. 918-1206, page 95, entry 280. The key phrase is "Geoffrey de Sai and of Geoffrey, son of the said Geoffrey and of Aeliza de Kaisneio."

3: Thomæ Stapleton, ed., Magni Rotuli Scaccarii Normanniae sub Regibus Angliae, Volume I (London, 1840), pages cxxiv and 90.

4: R. W. Eyton, Antiquities of Shropshire, Volume III (1861), pages 331-332.

5: The Publications of the Pipe Roll Society, Volume XXV (1904), page 55.

6: Monasticon Anglicanum [...], Volume V, page 73, footnote y, deed 1 ("The Deed of Geoffry de Say for the Manor of Dudintun")

7: Patent Rolls of the Reign of Henry III Preserved in the Public Record Office: A.D. 1225-1232 (1903), page 360. As you can see,

8: Thomas Duffus Hardy, Rotuli Normanniae in Turri Londinensi [...], Volume I (1835), page 63.

9: Thomas Duffus Hardy, ed., Rotuli Litterarum Clausarum in Turri Londinensi, Volume I (1833), page 102, right column.

10: Rotuli de Oblatis et Finibus in Turri Londinensi Asservati, Tempore Regis Johannis (1835), page 535.

11: Thomas Duffus Hardy, ed., Rotuli Litterarum Clausarum in Turri Londinensi, Volume I (1833), page 209, right column.

12: William Dugdale, Monasticon Anglicanum [...], Volume XI, Part 2 (London, 1846), page 913.

13: British Library Cotton MS Nero I, folio 123r

14: J. C. Holt, Magna Carta, 3

15: Rotuli Litterarum Patentium in Turri Londinensi Asservati, page 157, left column, halfway down the page.

16: ibid., page 158, right column, near the bottom.

17: David Carpenter, Henry III: The Rise to Power and Personal Rule, 1207-1258 (Yale University Press, 2020), page 50, footnote 162.

18: Douglas Richardson, Royal Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families, 2

19: Patent Rolls of the Reign of Henry III: A.D. 1216-1225 (London, 1901), page 80.

20: Thomas Duffus Hardy, ed., Rotuli Litterarum Clausarum in Turri Londinensi, Volume I (1833), page 321.

21: Tanya Dedyukhina, "Lincoln Castle" (photo taken 5 April 2007), Wikimedia, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lincoln_castle_-_panoramio_(1).jpg>. Ms. Dedyukhina has made this image available under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

22: Thomas Duffus Hardy, ed., Rotuli Litterarum Clausarum in Turri Londinensi, Volume I (1833), page 393.

23: Patent Rolls of the Reign of Henry III: A.D. 1216-1225 (London, 1901), page 369.

24: "Interior Catedral Santiago de Compostela.jpg" (photo taken 2 July 2006), Wikimedia, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Interior_Catedral_Santiago_de_Compostela.jpg>. This image has been shared under a Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 unported license.

25: Thomas Duffus Hardy, ed., Rotuli Litterarum Clausarum in Turri Londinensi, Volume I (1833), page 475.

26: Excerpt from: Ralph V. Turner, "William De Forz, Count of Aumale: An Early Thirteenth-Century English Baron," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Volume 115, Number 3 (17 June 1971), pages 221-249.

27: William Page, ed., The Victoria County History of the County of Sussex, Volume II (London, 1902), page 92.

28: Close rolls of the reign of Henry III [...]: A.D. 1227-1231 (London, 1902), page 431.

29: UK National Archives reference C 60/29, membrane 1, an entry labeled "Willo de Say." I downloaded an image of the relevant entry from the Henry III Fine Rolls Project at <https://finerollshenry3.org.uk/content/fimages/C60_29/m01.html> on 20 June 2022. You can read a transcription of this record in: Excerpta è Rotulis Finium in Turri Londinensi [...], Volume 1: A.D. 1215-1216 (1835), page 202.

30: Henry Richards Luard, Annales Monastici, Volume I, page 77.

31: William Dugdale, Monasticon Anglicanum [...], Volume VI, Part 2 (London, 1846), page 657.